Margaret Begbie

National Fire Service

Tadeusz Brylak

Polish Army

James Drysdale,

Gunner, Royal Artillery

Rudi's birthplace:

his grandparents' home in Voitsdorf.

Rudi and his mother at home in

Niemes, in the Sudetenland

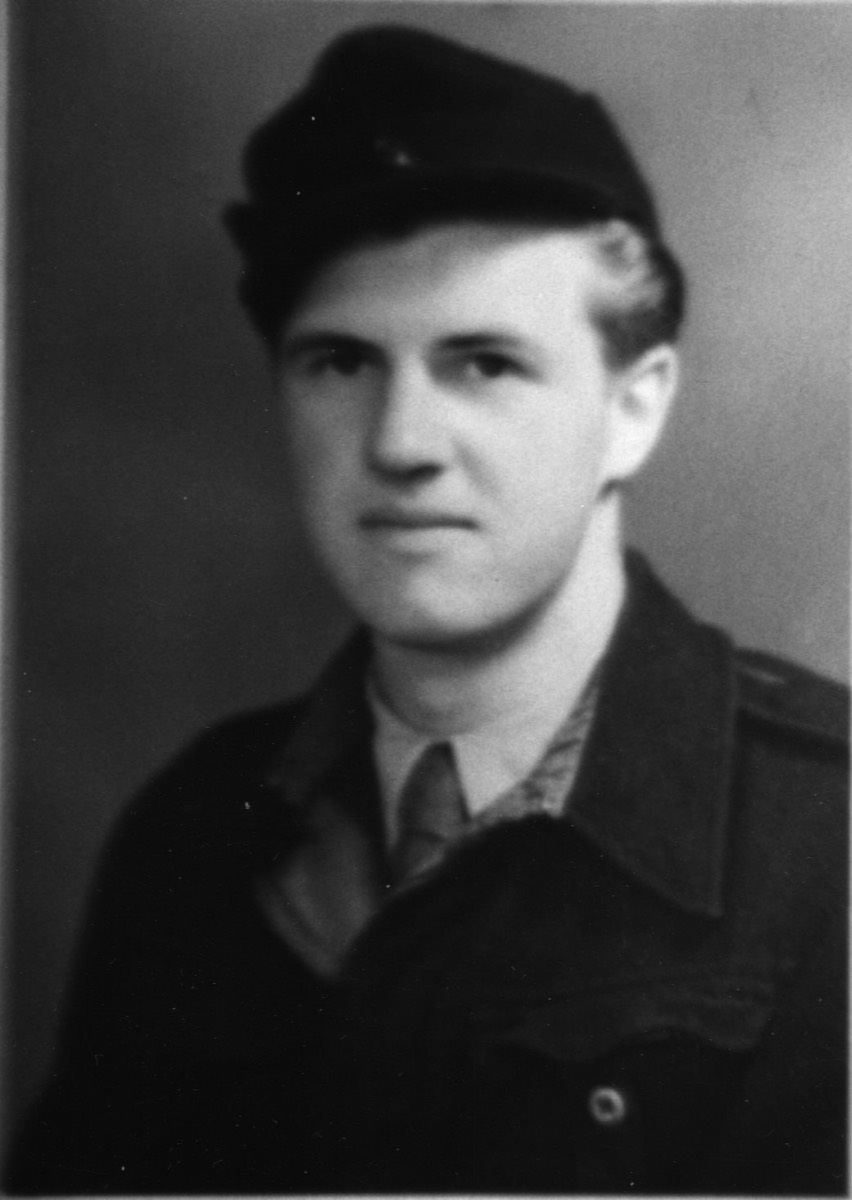

Rudolf (Rudi) Franzel

Unteroffizier Anwarter, 25th Regiment of the 12th SS Panzergrenadiers Hitlerjugend (Youth Division), 1943-45.

Rudi was used to and preferred to use the German names for his local towns and this can cause confusion nowadays, since they all lie in modern Czechia.

Niemes is now known as Mimon.

Voitsdorf is now known as Bohatice u Zakup.

Interviewed in Haddington by David Haire on Saturday, 29th March 2014, when aged eighty-nine. Rudi died in August 2019.

Early Years

Rudi was born on the 11th March 1925 and lived in Niemes in the Czech Sudetenland. He was born in Voitsdorf in his Great Grandfather’s house and in 1931 he went to the local school in Niemes. His father was a skilful machine engineer who repaired safes and his Great Grandfather was a herbalist healer who used his orchard and herb garden to help treat local peoples' illnesses. When Rudi was to be christened in the local church in Voitsdorf, his mother and father had to walk many miles through snow two metres deep carrying him all the way from Niemes.

The Sudetenland

When Rudi was young the political situation in Czechoslovakia had been complicated by the often challenging geo-political changes brought about by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the First World War. The Sudetenland, an area of Czechoslovakia bordering Germany in the west, was largely peopled by German speakers. It had formerly been part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, but the Empire’s defeat and collapse at the end of World War One had resulted in this area being included in the new state of Czechoslovakia.

Hitler was to make good use of this messy ethnic arrangement as an excuse to annex it in 1938 after Chamberlain, Daladier and Mussolini had signed the Munich Agreement acknowledging Hitler’s move. All this was to have far-reaching consequences for the Franzel family. It immediately made Rudi and his family liable to conscription into the German armed forces. As a foretaste of other effects, effects which were to rebound on the Franzels seven years later, the few Czech families in Rudi’s area were compelled to move away to the east into Czech dominated areas.

Rudi's home in Niemes

Rudi's family

In 1939, when war began, Rudi was just fourteen years old and initially it meant little to him personally, except that his father was sent north to Cuxhaven where his engineering skills were put to military use in the construction of torpedoes. His father was to serve in Gotenhaven (Gydnia now), in Keil and in Naples where he participated in testing torpedoes. Once at Gotenhaven he witnessed the Bismarck being armed, provisioned and loaded with torpedoes. Rudi’s younger brother was conscripted into the Navy and spent the war years laying mines, mines which, at the war’s end, he had to help recover. His uncle went into the army, as did cousin Pepe.

Rudi's uncle

Rudi's family paid heavily for supporting HItler's war. Not only did the family lose their home and suffer being split up, but his cousin Pepe was killed fighting partisans.

Hitler Youth

Rudi first came across the activities of the Nazis when he joined the Hitler Youth. This involved weekend activities and lots of exercise. As a youngster Rudi remembers pilfering iron grills and loopholes from the newly constructed Czech defences along the Czech/German border. Something, he admits, would have got him shot if he and his pals had been spotted.

Arbeitsdienst

Where Rudi lived was well known as a leather producing area and contained some forty-two tanneries. When he left school Rudi trained as a tanner but, on reaching eighteen in 1943, he was sent to join the Arbeitsdienst, the Reich Labour Service. This organisation was set up to help reduce unemployment, to provide useful military training and to help indoctrinate members in Nazi ideology. Rudi was sent to Poland where he helped clear woods and drain marshes.

Rudi (on left) with other soldiers while on Arbeitsdienst service in Wosow, Poland, 1943.

Flag of the Arbeitsdienst, the Reich Labour Service

Rudi (on the right) with his mother, a friend and his mother during his time in the Arbeitsdienst.

The Waffen-SS

However, Rudi only remained in the Arbeitdienst for three months before being conscripted and sent to a Waffen-SS NCO Training School at Lauenburg in Pomerania. He was, by this stage, a strong, well built man six feet two inches tall [1.89 metres]. After the training school Rudi was posted to the 12th Waffen-SS Panzergrenadiers Hitlerjugend (Youth Division) as a heavy weapons instructor and he was based with it in Belgium. His job was to train groups of thirty in different weapons, such as the infantry heavy machine-gun and the Panzerfaust (an anti-tank weapon).

Normandy

At one point he was transferred for five to six months to assist the Military Police. When the Normandy landings took place in 1944 he was sent to help direct traffic in Rouen as the German forces responded. This didn’t last too long as he was soon sent back to his unit, the 25th Regiment of the 12th Waffen-SS Panzergrenadiers, as it was hastily moved east to the Caen area to stem the British and Canadian troops mounting Montgomery’s offensive to take the city.

His first introduction to actual fighting came with being on the receiving end of a naval bombardment coming from the battleships, etc., of the invasion fleet lying offshore. He was then helping to defend what may have been Carpiquet airfield. He described how the air ‘…shuddered…’ with the huge concussions of the exploding shells. This bombardment may well have been the same one responsible for killing Fritz Witt, the commander of the 12th Panzer Division, when his divisional command post in Venoix was hit.

12th Panzergrenadiers

Despite a heavy preponderance of young soldiers in the 12th Panzergrenadiers, it was able to inflict considerable damage upon the Canadian advance, first catching a number of Canadian tanks in the open (an event Rudi witnessed) and fighting was very intense. Rudi described how the fighting ‘…put the wind up you.’

Being recruited largely from the Hitler Youth, the 12th Panzers contained a preponderance of young soldiers. However, they were stiffened by Regular army officers and NCOs from battle experienced groups from elsewhere. Rudi was, after all, only nineteen at the time. When asked to comment on the youth of his regiment and division, Rudi said that, ‘…they were young but you could depend on them.’

Close shaves

Given the nature of the terrain, much hedged and dyked, it's not surprising that Rudi had a number of very close shaves. He described lying on the ground on one occasion when a bullet hit the ground just between his legs. As he said, jokingly, ‘I got out of there fast!’ On another occasion, again in the type of terrain typical of 1940s Normandy and called ‘Bocage’ by the French, Rudi needed to go to the toilet. He jumped up on top of a wooded bank and went through the undergrowth and found himself right beside a British mortar team! Another experience requiring a very quick exit.

The battle for Caen

German resistance, however, was unable to hold the Allied advance and the front line retreated until the Germans were holding onto the town of Caen itself. Rudi described how the battle stalled for around a fortnight, both sides exhausted by their efforts. He was in the Caen area for around a month. To break the stalemate, Montgomery ordered the RAF to launch a major assault on the German held positions in Caen itself and Rudi remembers seeing the Lancasters, etc., droning into position over the city and thinking that if they attacked he’d have to find a place to shelter, quick. He saw the bombs drop from a number of planes before diving for cover. Rudi was hit by a large splinter of wood, ‘…as sharp as a knife.’ and it sliced through his gas mask which he carried by his hip. He carried the splinter for a while as a ‘lucky’ mascot but soon grew tired of it and threw it away. He was involved in the battle for the town and in three days of house to house fighting.

20th July plot - reactions

On the 20th July 1944 the plot to kill Hitler was activated and Lieutenant Colonel Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg planted his briefcase bomb. It failed to kill Hitler but there was considerable confusion until Hitler was able to make it clear that he had survived. Rudi remembered a German regiment behind the 12th Panzers (which must have been led by officers supportive of the conspiracy) turning their guns on him and his men. Only the news that Hitler had survived and careful negotiation saved the day, no shots were fired and the other regiment moved away.

Escape from Normandy - evading the trap at Falaise

The fighting around Caen intensified and Rudi and his platoon of seven men found themselves cut off from the rest of the regiment. He was able to lead them to safety through three Allied defence rings by walking only at night and hiding in woods during the day until they reached the Seine. At times the group had to remove their boots to avoid any noise as British troops were all around them. They evaded discovery and found an old civilian bus with a dead man lying in it. Luckily the key was in the ignition and the bus started.

The retreating Germans had blown most of the bridges but had left one open to allow soldiers like Rudi to escape. They thus drove back to the safety of the northern side where he was back among his own troops. The 12th Panzer Division had gone into the maelstrom of Normandy with some 20,540 men and came out of it with only 12,000, a loss rate of 42%. It had lost ninety-four per cent of its armour and almost all its artillery. It was sent back to Germany to regroup and rebuild. Rudi went with it to Kaiserslautern.

Battle of the Bulge, 1944

By the winter of 1944 the regiment had returned to full strength and it was sent to form part of the army which would attack through Luxemburg in Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein (Operation Watch on the Rhine), in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. Sepp Detrich became Rudi’s commander. Rudi reached Luxembourg city but on approaching a cross-roads beyond it on Christmas Eve, 1944, he was shot in the leg.

Before this he remembers an incident when an American convoy carrying supplies of food, etc., was caught in a German attack which was later repulsed. The lorries carrying the food sat for a while in a brief No Man’s Land and Rudi and his colleagues risked their lives to get out to the lorries and retrieve the food. Since the Americans were trying the same it provided some interesting moments. Rudi also remembers seeing Germans dressed in American Army uniforms misdirecting American traffic. As he said, ‘I didn’t see them again!’ Many of these, when captured, were shot as spies.

Fate of the 12th Panzergrenadiers

Rudi was taken to a Field Hospital from which he was supposed to be taken to a proper hospital in Nimen [sic, perhaps Meissen?] but, as the train drew closer to Dresden, Rudi could see the flames of the city as it was being bombed and the train diverted to Oldenburg. While he was recuperating in hospital Rudi’s unit was sent to Hungary where it came up against the Russian Army. Rudi was glad he didn’t go with them as few came back after the war when the Russians captured them and took them to PoW camps in Russia.

Facing the Allied advance

Meanwhile the Allied advance had progressed and Montgomery attempted to cross the Rhine at Arnhem. Although that failed, it was only a temporary setback and word reached Rudi that the Wehrmacht was in retreat. Being part of the Waffen-SS, which included some of Hitler’s most dedicated soldiers, Rudi was ordered in the opposite direction, towards the advancing Allied armies.

Injuries

He had a very lucky escape when he was occupying one of two fox holes side by side with another soldier while they were helping to defend Luneberger Heide. It came to Rudi’s turn to eat and he exchanged the role of look out with his neighbour. While Rudi ducked down for shelter and food his companion stood up to use his binoculars. Rudi ate his food and then tapped the soldier on the arm only to find he was dead, shot by a sniper through the temple. Rudi, of course, realised it could so easily have been him and was puzzled by the complete lack of sound. He had heard nothing.

He didn’t escape injury for much longer, however, as he was hit in the ankle by aircraft machine-gun fire. He was lying on the ground as the aircraft strafed the area and schrapnel from the aircraft’s cannon shells must have hit a nerve because his leg suddenly jerked forwards and he thought his leg had been blown off. This happened a week before the end of the war. Ironically, the schrapnel pieces lodged in his ankle were finally removed in the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh!

The end of Rudi's war

Rudi’s war finally ended three days later when he surrendered to a whistling and singing platoon of American soldiers on Luneburg Heath near Munster. Rudi was hiding among some fir trees with a young Austrian soldier by his side when the platoon came along the road. Not wishing to be shot, Rudi stayed low and shook a branch to attract their attention and they all dived for the ground. After taking him prisoner the Americans sent him to a nearby PoW camp and later he was handed over to a British unit and taken to another PoW camp at Berchem, in Antwerp, Belgium.

PoW camp, Berchem

[Ed. This phase of Rudi's wartime experiences was probably his toughest and personally most unpleasant. All SS were hated and were treated very badly. When interviewing him on a previous occasion at Amisfield in Haddington, he refused to talk about his experiences at Berchem. Clearly they were simply too painful.]

This camp, for some 10,000 prisoners, was established on part of a hill which had been flattened by a V2 rocket explosion. (1) Rudi had to sleep in a tent and dig into the ground for protection as the Belgian guards had been known to shoot indiscriminately into the camp. He saw some Germans sunbathing being shot in this arbitrary way. Conditions there were very bad and there was little food. The Commandant of the camp was later arrested and imprisoned for siphoning off food intended for the prisoners, in order to sell it on the Black Market. The Belgians had, understandably, little love for their charges at this time. Rudi was kept there till April 1946 and the International Red Cross later shut the camp down.

1. This may well have been a V2 fired by Battery 2/836 based at Merzig, Greimerath (site 202) on Wednesday, October 25th 1944 which was aimed at Antwerp and which fell at Fruithof, Berchem.

Rudi Franzel as a PoW in Gosford

Gosford PoW camp 16

Rudi was sent from the camp to Ostend, by ship to Tilbury docks and then by train to Longniddry and Camp 16 in the grounds of Gosford House. After Berchem, Camp 16 was, ‘…brilliant!’. Rudi was just skin and bones when he arrived on the 23rd April 1945 and he was forbidden to work for six weeks. He was simply too weak. He was surprised and happy to meet a former colleague from the NCO Training School at Lauenburg who’d come to the camp a day earlier. This man had trained as a wireless operator and was a linguist too and he helped Rudi get his German Army pension later on. It wasn’t the first time Rudi had met this man. He had met him while Rudi was directing traffic in Rouen during the battle for Normandy. Rudi had told his friend to go and sit in a café and came across later to chat.

Work details

When he had recovered he was allowed out of the camp on a variety of jobs, the first of which was working for the Quartermaster in Edinburgh Castle. From him he was able to obtain strips for the camp’s football team. Each day a civilian would arrive at Gosford with a lorry and take Rudi and others to do some job or other around the county.

To eek out their rations the prisoners needed to get their hands on Sterling. This was not permitted, but that didn’t stop the prisoners from trying. Some made toys in the camp and Rudi remembers taking ammunition boxes full of these toys out of the camp to sell on Arthurs Seat in Edinburgh. He said they disappeared fast. Part of the cash went on buying beer, what he called Fliers Beer. Later Rudi went to work with five other PoWs on Upper Kieth farm near Humbie, where he worked from April till August, 1947. Eventually he was allowed to remain on the farm when the British Government permitted ex-PoWs to remain in either farming or fishing.

An example of the kind of toys made by German PoWs in East Lothian. This one was made in Amisfield, Camp 16A

No going home

Rudi decided to remain in Scotland. He’d been well looked after here and had not experienced the difficult reception many Germans had faced in other parts of the UK. He only discovered what had happened to his parents in 1948 when he received a letter at Christmas time from his mother in East Germany telling him that the family didn’t have enough room for him to return. At the end of the war his mother and sister had been forced to leave their home in Niemes within twenty-four hours and had had to leave everything they owned behind. She also advised him against coming home as he would probably have been arrested by the authorities and sent off to Russia, as so many former German soldiers had been.

Rudi's daughter, Effie wrote: "My Omas's (grandmother's) neighbour was stoned to death with the children and another friend shot. Dad had no home to go back to. He was classed as a Displaced Person and the British Government invited him to stay. [Years later] he went back to visit his home town. Their family home, which, of course, still belonged to them, was still standing, but now with a Czech family living in it."

Freedom

Life had been getting better for Rudi as the regime at Gosford had steadily relaxed, until the guards were finally removed in 1947. He had been allowed to walk out unsupervised on Sundays and had even met a local girl, Betty Young from Haddington, on the farm when she was picking potatoes and he was driving the horse and cart. He got married to her on 30th October 1948, just before his release from Gosford.

Rudi has worked and lived in his adopted East Lothian ever since, some years on the farm and over thirty in the Maltings in Haddington. He said that he didn’t find settling in as hard as one might have expected. Perhaps working in the relative obscurity of the countryside had helped.

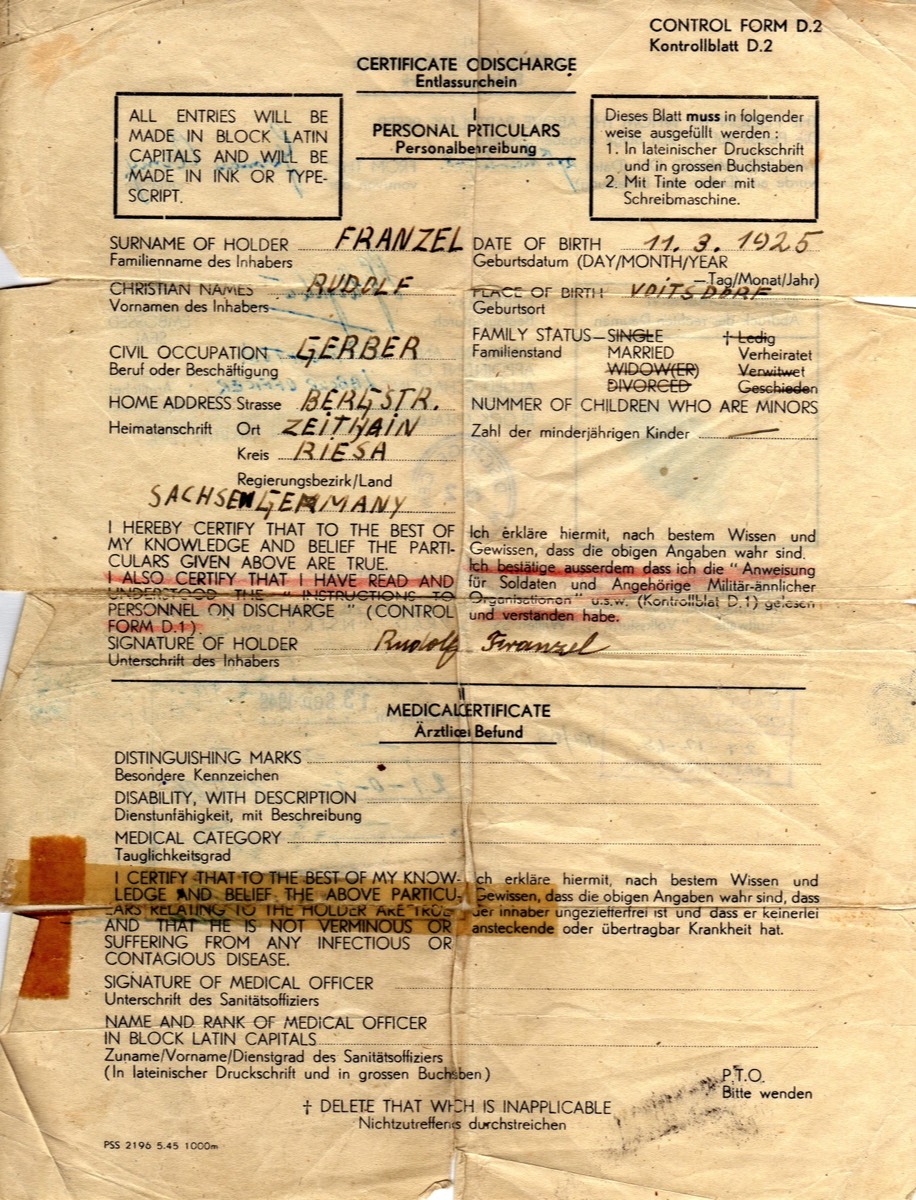

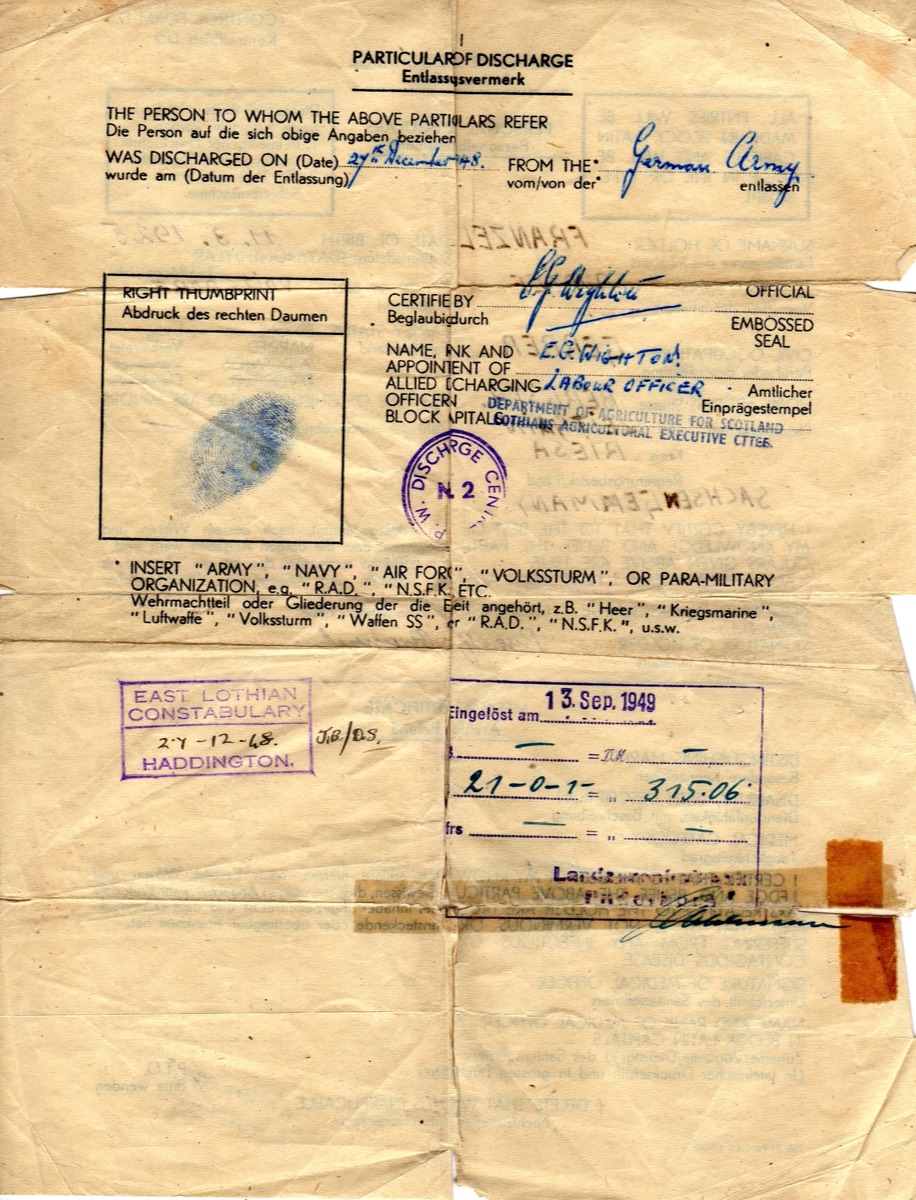

Rudi Franzel's PoW discharge papers, 27th December 1948

David Haire with Rudi Franzel and Gunter Schumacher when Rudi and Gunter revisited the site of Amisfield PoW camp 16A.